I'm a trans person, and like all trans people, I'm freaking out. In the UK, organisations that have recently moved to ban trans women and girls include: The Girl Guides, The Labour Women's Conference, and The Women's Institute. At the same time, Gender and sexuality are boxes that will never be able to contain us, and arguably were never meant to.

This reality scares the shit out of people, including me.

Transphobia is rife. I knew it, and now that I've begun the process of coming out, I feel it. Interestingly, I have never felt less ashamed of myself, but never have I been more the subject of attempts to shame me. As I increasingly come to recognise myself, there are so many who refuse to see me. Trans people, our allies, and those who oppose us are at an impasse. As the fallout from this deadlock grows more frightening by the day, we urgently need to understand the chasm between us. We need to confront what hides in this shadowy place—particularly the monsters residing in the deepest corners of our shared psyche. This will also mean daring to look into the most frightening place: the mirror.

Every day, alarming news stories reinforce our justified sense of being othered and targeted, heightening our states of hypervigilance. A doom scrolling session will confirm that the transphobes are not changing their minds—or if they are, they are very quiet about it. In fact, it feels like they are doubling down. Meanwhile, we are taking stock, gathering allies. We are pulling our found families closer, increasing our safety networks and enhancing our hormone-seeking black market know-how, homebrewing technologies, and setting up our surgery fundraisers. It is among this shitshow that I'm coming out at the age of 40 as nonbinary trans masc. It has only been a few months, yet I've already reached peak freak-out. Transphobia has moved in. Friends have turned on me, and I'm a victim of vitriolic text messages from people I thought loved me. My coming out has mostly been met with affirmation and celebration. Mostly. However, with one friend—I'll call him Paul here—the rupture has felt particularly crushing.

"Why should I celebrate you?" Paul asked flatly, his head angled to the side. In many ways, it wasn't shocking that this was going badly since I knew Paul's views on trans rights. His takes on trans women were particularly horrendous and had been worsening over time, especially since COVID. I went into the coming-out meeting I had been dreading for a long time, hopeful that humanity could win. I decided to give him a chance because of our history, and in honour of the kindnesses he had shown me in the past. So, I sat across from him at the table, peppermint tea in trembling hand. He eventually looked up from his cappuccino. I was determined to keep eye contact as I answered him—even if I felt my conflict-resistant insides liquifying, screaming at me to look away. And there it was— the monster roaring in the blacks of his pupils.

"I don't need you to celebrate me," I replied. Of course, that's bullshit. Of course, I needed Paul to. We travelled through the circular arguments, and I heard how deeply he was in his transphobia. It became clear to me that he was incapable of seeing me as a human being. I even tried telling him my history of domestic violence and sexual assault—which I hadn't previously disclosed—in a bid to persuade him that cruelty to trans people was counterproductive in the fight for women's safety. I tried talking about the vigil I had been to for Trans Day of Remembrance in London's Soho Square, where I heard too many heartbreaking stories of trans youth dying by suicide. He was unmoved, and I was devastated. I suspected that he was too lost in his own suffering. So much so that he couldn't see anyone else's. That was the very human place I had hoped we might have been able to meet, but I knew as I walked out into the cold, that it wasn't to be.

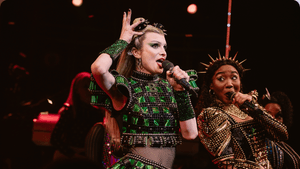

It's a lot easier, and oh so tempting, to just conclude that transphobes are simply monsters, and I am not. They are the bad guys, and I am on the good side. This is, of course, too neat and not true. We are all children of Frankenstein. We know the humanity of the monster, and the monstrosity of the human. In dissecting the monster, I'm inclined to focus on our collective ability and potential to shift or bend. The omnipresent beautiful possibility of spilling out of the box, leaking from it, to switch boxes, to create more. Whilst many of us might be excited by this possibility, the rest—including myself—would feel safer if we were to remain in the box. I'm reminded of performer and artist Travis Alabanza's words: that it is society, not us, that makes us trans. We are made trans by the norms that we transgress, which were imposed upon us, and we then always exceed. We did not choose this.

And when I say this, I mean this specific experience of being trans and the reactions we might receive to moving our bodies into alignment with our sense of who we are. The bodies of my gender and my desire are intertwined threads—all up in each other's business. They fuck with and against each other, and what they produce can be at once unpredictable and wondrous—monstrously frightening—in its potential.

Alok Maid-Venon writes that trans defiance of society's rigid expectations—rules that the transphobes must also follow—is too much of a provocation for them to bear. As Alok also writes, transphobia is a means of detouring from the pain of the realisation that these colonial gender-boxes are destructive and hurtful to individuals and societies—including the transphobes themselves. Judith Butler writes in Who's Afraid of Gender that transphobia has become a kind of phantasm into which is projected all the significant hurt and fury suffered by society, with the result being the demonisation of trans people. But I am left wondering what happens to trans people's suffering and hurt? What am I to do with my poisonous, all-too-human, all-too-justified in the destructive world-place in which we live, projections?

What happens is they become internalised as the voice from within that calls me a freak in the mirror. Or, they fuel the way I judge other trans folk who might not conform to my idea of what being trans looks like and compartmentalise them as bad queers/bad at being trans. My internalised toxic cis-normativity feeds the gender-cop in my mind. To survive, part of me becomes like one of them.

Them and us. Good and bad. The classic splits that blight all human communities—the barricades across which we fight and love. Because of our human tendency to label someone as good or bad, holding contradictory feelings about a person can be hard. Everyone is either good or bad, and there's little tolerance for ambivalence. Being trans means to be split within, and to be split by others. We are loved by many and hated by many. In being either intensely revered or despised, we are not afforded the luxury of being that all-too-human mixture of good and bad. It's difficult, being wholly angel or demon—when every day I am mostly both.

But there is some hope, I believe. In recent days, there have been some climb-downs, notably from the texting transphobic family member. They have expressed a desire to understand, at least. The damage, however, is already done. I'm still angry, and part of me wants to say, "Fuck you—you're bad, I'm good, and why should I bother building a bridge to you? Let it fucking burn." The monster in me. The roaring chimera. I know it isn't right for this split guy within to be my guide, no matter how tempting—no matter how justified. I have to act despite my anger at the collective unconscious for having made me the more monstrous monster.

What of my former friend, Paul? Well, I admit that I do hold hope for repair in the future. I have to. My relative privilege as someone who is white and trans masculine—not trans feminine, as so much of the fear-driven discourse around women's rights and TERFism is directed at our beautiful sisters—means I feel a responsibility to hold onto hope. Hope so that I might keep on doing the talking, sometimes. We who have to keep trying.

As a parent, I have to hold hope for the possibility of change so that children of queers can build the queer futures we dream of. As a writer, I have to believe in the power of conversation and the intimacy of sitting face-to-face with another—even when we're shrouded in darkness and the monster's roar threatens to drown out our voices.

Vic Brooks is a nonbinary writer living in London and parent to small identical twins.

Perspectives is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Pride.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Perspectives stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Pride or our parent company, equalpride.