When you think of the Civil War, you might think of Gone With the Wind or a Ken Burns documentary, but most likely not of LGBT history — and art teacher Scott Angus is out to change that.

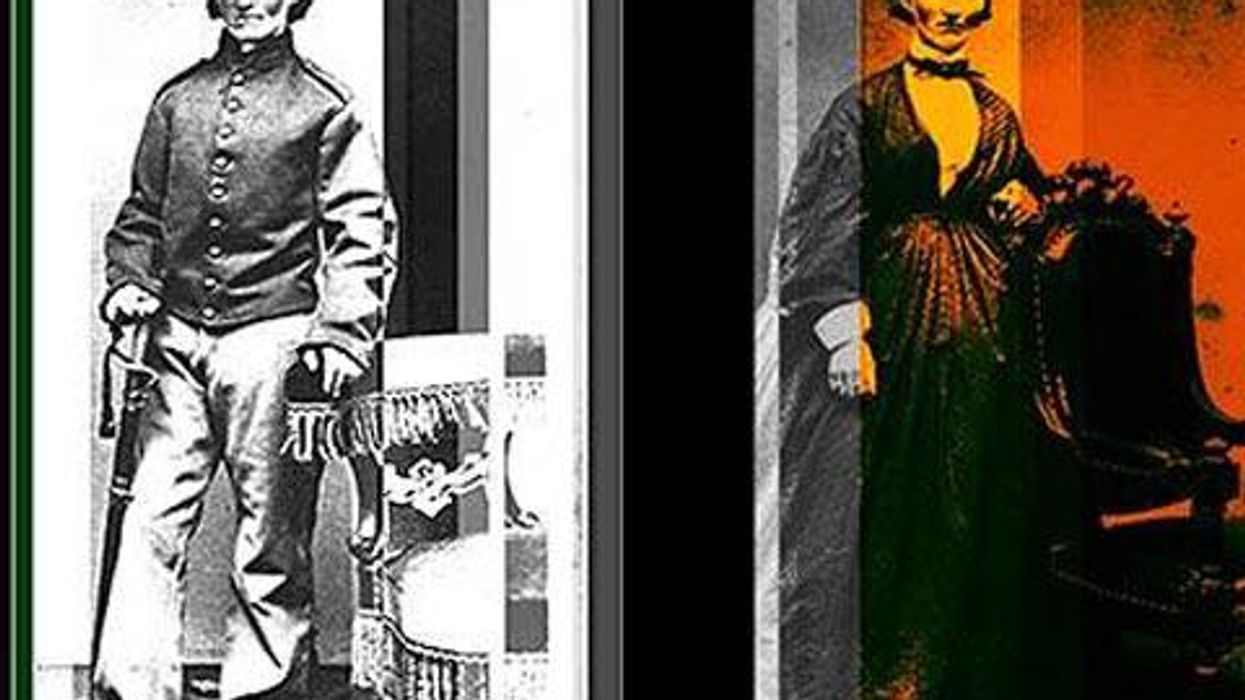

Angus has collected images of women who dressed as men to fight in the war and modified them slightly with colors representing the modern transgender rights movement for an exhibit called “Forgotten Heroes,” being displayed throughout November at the Metropolitan Community Church of Greater St. Louis for Transgender Awareness Month.

“The story of GLBT causes doesn’t start with Queer as Folk,” says Angus, an assistant professor of studio art at Maryville University in St. Louis.

Angus, who is gay, became interested in cross-dressing Civil War soldiers after happening upon a few images of women who presented as male in order to fight in the conflict. Additional research showed him the phenomenon was widespread — U.S. government records document that at least 800 female-bodied soldiers served on the Union side alone. There were also some who fought for the Confederacy; various sources estimate the number at 250.

It’s difficult to say how many of these soldiers identified as lesbian or bisexual, or as transgender men, he notes. Such concepts weren’t even recognized at the time. He has found evidence, though, that at least a couple of the female-bodied soldiers featured in his exhibition identified as male and lived as men long after the war was over.

“Even though the identity of either a gay male or a lesbian or a bisexual or a trans person did not exist at this time, they did exist,” says Angus.

With the photos, which he previously exhibited at his university and hopes to take to LGBT centers around the nation, he seeks to recognize these soldiers as pioneers in the movements for women’s and LGBT equality. The people in the photographs might identify as lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or straight, he says, but he is confident all would identify as feminists. Assuming a male identity allowed a degree of freedom unknown to women in the 19th century.

“The American Civil War defined that America was a nation of equals, but it has taken and is still taking more than a century of activism to achieve equality for all,” Angus writes on his website. “These soldiers are an essential thread to the fabric of social justice in the American Experience. It is time they are remembered.”

Wes Mullins, senior pastor of the St. Louis MCC, also notes the importance of remembering these soldiers. “I want to ensure that all LGBTQ folk remember and are empowered by the knowledge that our people have been a part of history since the beginning of time, he says. “Telling these powerful stories from the Civil War was a perfect way to shine a light into history and into LGBTQ lives.”

He notes that there is still bias against transgender people on the part of some lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. “Our church wants to be sure that we are providing the necessary education to ensure that transgender folk are fully welcomed and supported in worship, in the broader LGBTQ community, and in society as a whole,” Mullins says.

And in a poignant nod to the situation in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, he adds, “Being in St. Louis, our church wants to embody the message that all lives matter — black lives and trans lives. Having Scott’s show in our gallery and hearing the stories of these forgotten heroes helps us realize what is at stake. We can either change history or be written out of it.”

Below and on the following pages, meet some of the soldiers in the exhibit. Because of the difficulty in knowing exactly how they identified and what pronouns they preferred — a difficulty Angus acknowledges — male pronouns are used for those who were known to live as men, female pronouns for others.

Albert D. Cashier

Albert D. Cashier, an Irish immigrant who was born Jennifer Hodgers, served throughout the war with the 95th Illinois Infantry — and quite bravely. Although smaller than his fellow soldiers, Cashier “never avoided danger” and sometimes “seemed to court it,” but managed to never be seriously wounded, according to New York Times Disunion blogger Jean R. Freedman. He was captured by Confederate forces during the siege of Vicksburg, Miss., but seized a gun, fought off his captors, and ran until he was reunited with his Illinois unit. The Union victory at Vicksburg in 1863 helped turn the tide of the war in that side’s favor, as it gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, and Cashier’s name is among those carved into the Illinois monument on the battlefield. He went on to serve in campaigns in Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alabama.

After the war he lived in various towns in Illinois, eventually settling in Saunemin, about 80 miles southwest of Chicago. He made his living with whatever type of work he could pick up, such as farm labor or general handyman work. His neighbors readily accepted him as male, just as his military comrades had. However, in old age he moved to a veterans’ home in Quincy, Ill., where his female anatomy was discovered, and he was therefore diagnosed as mentally ill. He was sent to a mental institution in Rock Island, Ill.; there he was put in a straitjacket and forced to wear dresses. His fellow veterans petitioned for his release, but Cashier died (in 1915) before his case could be heard. They did, however, succeed in having him buried as Albert Cashier, not Jennie Hodgers, in his soldier’s uniform and with full military honors. “Today it can be determined she/he would be a transgender person,” Angus says.

An image of Albert Cashier as a soldier, transposed over the mental hospital where he was committed in old age and forced to wear dresses.

Frances Clayton

Frances Clayton was, according to Angus and other historians, a straight woman who joined the Union Army so she could be with her husband, Elmer; she would eventually witness his death in battle. She called herself Jack Williams and served with Missouri forces. The record of her service and the rest of her life is sparse, but she is the only female Civil War soldier who sat for studio portraits in both men’s and women’s garb. Angus notes that if there had been a concept of gay male identity at the time, she and her husband would have appeared to be a gay couple; men could be openly affectionate and even sexual with each other, and such activity was labeled bad behavior rather that an indicator of a person’s identity. “Today Frances Clayton would be straight, but in an odd twist of fate she can be argued to be an early hero for the rights of gay men,” he says.

Franklin Thompson

Franklin Thompson was born Sarah Emma Edmondson (later shortened to Edmonds) was born in Canada in 1841. To escape an abusive father (he had wanted a son) and an arranged marriage, she left home as a teenager, and she eventually disguised herself as a man and took the name Franklin Thompson. In Hartford, Conn., she found work selling Bibles. By the start of the Civil War, she was living in Flint, Mich., and as an ardent supporter of the Union cause, she joined the 2nd Michigan Infantry as Thompson. She served primarily as a courier and medical aide in battles including First and Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Williamsburg, but this was still dangerous work, and she occasionally had to pick up a weapon and join in the fighting. In the spring of 1863 she came down with malaria, a common ailment during the Civil War, and to avoid discovery of her female gender during treatment, she left the Army, according to an article on the Civil War Trust’s website. After she recovered, she began living as a woman again and worked as a nurse. She wrote memoirs of her service in which she claimed to have been a spy, but there is “no definitive proof” of this, the article notes. She had many known relationships with women, Angus says, but after the war she married a man named Linus Seelye, and they had three children. The U.S. government, though, recognized her service as a man. Her former comrades in arms successfully campaigned to have her cleared of desertion charges, and through an act of Congress “Franklin Thompson” was awarded a retroactive honorable discharge and a military pension, Angus says. Thompson/Edmonds was buried with full military honors in Washington Cemetery in Houston in 1901.

Unidentified Civil War soldiers; the one in the middle is a gender-crossing service member.

Below, watch a video of Angus’s talk with Mullins at the St. Louis MCC earlier this month and get to know more of his subjects, including Lyons Wakeman, the first known transgender soldier to be killed in battle and buried with military honors in a national cemetery,

11-02-14 - Sunday Sermon from MCC of Greater Saint Louis on Vimeo.

Cindy Ord/Getty Images

Cindy Ord/Getty Images