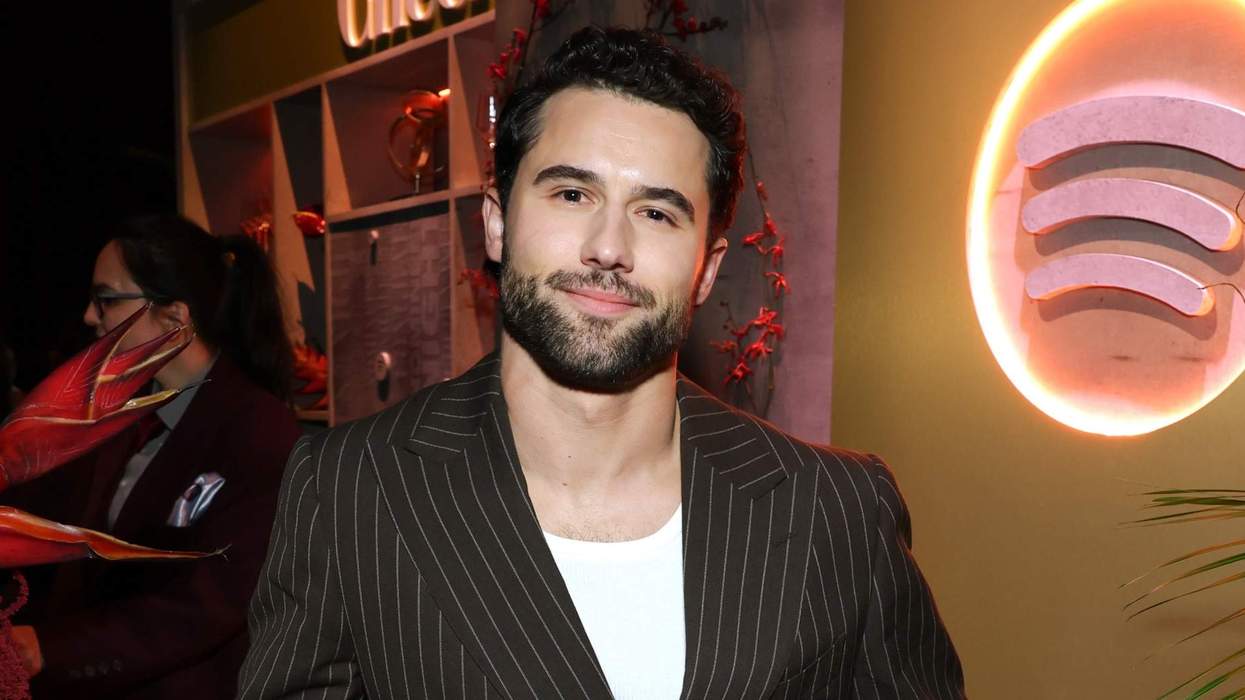

As an HIV-positive gay man, Daniel Garza was accustomed to being judged for his lifestyle and not listened to by doctors, but what he didn’t know was that this negligence would put him at risk for getting cancer.

The LA-based Latino American actor and comedian was diagnosed with HIV in 2000, but it wasn’t until 15 years later that he would face a second diagnosis that almost went unchecked because of the stigma surrounding gay sex.

“In my personal experience with anal cancer, my symptoms were initially assumed to be associated with foods I ate as part of my Latino heritage and with my lifestyle being a gay man,” Garza tells PRIDE. “However, I kept pushing for answers because I knew something was wrong.”

At the time Garza was diagnosed with stage 2 anal cancer, he had been an HIV advocate for more than two decades, and yet no doctor had ever told him that being HIV-positive put him at an increased risk of developing anal cancer. “I wish I had known this sooner,” he says. “That is why I now use my platform to raise awareness of key risk factors of anal cancer and the importance of self-advocacy.”

After being diagnosed with anal cancer, Garza went through 38 rounds of radiation, two weeks of chemotherapy, and 40 rounds of hyperbaric chamber treatment to rejuvenate his cells.

Garza’s own harrowing experience of having his doctors almost miss the fact that he had cancer because of their biases around men who have sex with men led him to start fighting to raise awareness around the risk factors for anal cancer and the importance of self-advocacy.

“While I’ve always been open about having anal cancer, talking about it hasn’t always been easy,” Garza says. “Throughout my journey, I’ve dealt with challenging stigma that has underscored the need to have honest conversations with my healthcare team. It’s important for people to feel they can speak openly about risks and symptoms with their doctor as there are treatments available for anal cancer, including advanced stages. If you aren’t getting the care you need, don’t be afraid to seek out a second or even third opinion.”

Ground Picture/Shutterstock

Despite this experience, Garza claims he had an excellent doctor; he just wishes that the link between HIV and anal cancer had been laid out for him. “I think it was because, at the time, there wasn’t as much information available, and I was not in the typical age range yet. Come to find out, people living with HIV are 25 to 35 times more likely to develop anal cancer than people not living with HIV,” he says.

Now, Garza is trying to make a difference as the director of anal cancer and HPV outreach at Cheeky Charity, which offers mental health services and anal cancer education geared toward the LGBTQ+ community, and is currently is partnering with Incyte on Let’s Talk Anal Cancer, a program aimed at normalizing candid conversations about anal cancer and providing critical information, particularly to LGBTQ+ folks.

As an anal cancer and HIV advocate, Garza uses his platform to talk to the Latino community to help “break down the barriers around having open conversations, which are culture, religion, and social norms,” and works to educate gay men about risks they might not be aware of. “When it comes to the gay community, I talk to men, especially submissive bottoms, about the importance of getting checked because once you’re diagnosed with cancer below the belt, it affects your sexual identity,” he says.

Garza also believes that his comedic background helps him to reach people who might otherwise not be receptive to his message. “My anal cancer education includes comedy, I make a lot of 'butt jokes,” he explains. “I want people to have conversations about anal, penile, and testicular cancers. As a society, we don’t want to talk about anything below the belt because it can be seen as stigmatizing and shameful, like you shouldn’t bring it up. But it’s important for people to feel they can speak openly about risks and symptoms with their doctor as there are treatments available for anal cancer, including advanced stages.”

But mostly, Garza wants to save other people from going through the medical procedures and health complications he experienced. “Please don’t miss out on the opportunity to get checked regularly — it’s all just a small fraction of your life versus living with cancer,” he says. “As a cancer survivor with an ostomy bag, my life has changed forever, and I don’t want that for you. Be uncomfortable for just a little bit so you can live a better life.”

Are people who are HIV-positive more likely to get anal cancer?

GaudiLab/Shutterstock

People living with HIV have higher rates of anal cancer and it is also more common among men who have sex with men, “particularly in those who engage in receptive anal sex, than in the heterosexual population,” Dr. Naomi Sutton, who works in the HIV and sexual health space for Sagami, a Japanese condom company, tells PRIDE.

This is in large part due to the connection between anal cancer and the Human Papillomavirus (HPV), which is transmitted through sexual contact. Around 90% of anal cancer cases are linked to HPV, a very common virus with over 100 subtypes. Most people have been exposed at some point, but in most cases, your body is able to clear the virus on it’s own, often without you ever having experienced a symptom. “Especially in individuals with HIV, the immune system may have more difficulty eliminating the virus,” she explains. “Over time, certain types of high-risk HPV can cause abnormal changes in cells that may eventually develop into anal cancer.”

Do doctors sometimes incorrectly dismiss symptoms like bloating, pain and bleeding because of stereotypes around gay sex?

Bleeding, itching, pain, discomfort, small lumps or ulcers in or around the anus, discharge, and difficulty controlling bowel movements are all common symptoms of anal cancer. The problem is that they are also symptoms of other conditions like hemorrhoids, which is why doctors and other healthcare professionals need to “remain vigilant for potential red-flag symptoms and ensure that appropriate examination and referral are carried out regardless of a patient’s sexual orientation or sexual activity,” Dr. Sutton says.

But men who have sex with men are 20 times more likely than heterosexual men to develop anal cancer, and HIV-positive gay men are up to 100 times more likely than the general community, according to Health Equity Matters.

Unfortunately, a survey done by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2024 also found that queer people are twice as likely as non-LGBTQ+ adults to report negative experiences while receiving health care, and are more likely than non-LGBTQ+ adults to report adverse consequences due to negative experiences with health care providers.

“Doctors are people too, and can have biases around gay identity and gay sex,” says Andrew Spieldenner, the executive director of MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights. “Doctors can sometimes dismiss symptoms due to stereotypes around gay sex — basically, that we must be bottoming a lot to have bleeding and pain in our rectum.”

Spieldenner says this judgment around gay sex led to similar misconceptions when the Mpox outbreak was happening. “We saw this in the Mpox outbreak where medical providers diagnosed syphilis instead of looking for Mpox,” he explains. “It is up to us to advocate for our needs, including finding another medical provider if we have to.”

If you think you may have anal cancer, what tests should you ask your doctor for?

PeopleImages/Shutterstock

Since most anal cancer stem from HPV, if you are having symptoms, you should first get an anal swab to check for abnormal cells and HPV. Your doctor or healthcare provider will probably also want to do a Digital Rectal Examine (DRE), where a doctor will insert a gloved, lubricated finger into your anus and rectum to assess whether you have any growths, lesions, or other abnormalities in the anal canal or surrounding areas.

Then, if you or your doctor suspect you may have anal cancer, you will likely be referred to a specialist who can perform additional testing, such as an anoscopy or proctoscopy. “Anoscopy involves inserting a small magnifying instrument into the anus to examine the anal canal, and sometimes small tissue samples (biopsies) are taken under local anaesthetic. Proctoscopy is a similar examination that helps identify any abnormalities,” Dr. Sutton says.

If a tumor is found, you may also need to get imaging done, like a CT scan or MRI, which will help your healthcare team determine the size and location of any tumors and whether the anal cancer has spread (metastasized) to other parts of your body.

Now in his 50s, Spieldenner has added cancer screening to his regular annual check-up, and when his doctor found abnormal cells in his anus during a routine anal swab, further testing was needed. “I ended up getting an anoscopy and then a biopsy of the tissues. I was anxious, but the procedure itself was straightforward,” he reassures.

Early detection is really the key since the sooner cancerous cells are detected, the better your outcome is likely to be. HPV and anal cancer are so closely linked that you should be vaccinated against it (especially since condoms don't provide total protection against it), and early testing can reveal precancerous changes known as Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN), which can often be treated to prevent it from progressing into cancer, according to Dr. Sutton.

Is it important to advocate for yourself with your doctors?

Talking about health problems is often challenging and can feel overwhelming, and this is only magnified when the health problem stems from a part of the body we are reluctant to talk about openly, but learning to advocate for yourself in a healthcare setting might just mean you’re able to catch cancer when it’s still treatable.

“It’s important for everyone to understand what’s normal for their own body and to feel confident in speaking up about any concerns,” Dr. Sutton recommends. “Keeping a record of your symptoms — including when they began and how they have changed over time — can be very helpful. This information allows healthcare professionals to better distinguish between different conditions that may cause similar symptoms.”

And if you feel like your healthcare provider isn’t listening to your concerns, is ignoring your symptoms, or may not take you seriously because of your sexual orientation, it’s time to get a second opinion or find a new doctor.

If you are having symptoms but are embarrassed to talk to your doctor about it, what should you do?

Lomb/Shutterstock

If you’re too embarrassed to bring up the possibility of anal cancer with your doctor or are feeling nervous about it, Spieldenner recommends practicing with a friend first. “Explain what you are concerned about and discuss your options,” he says. “Make a plan to build up to discussing with your doctor. You can always email concerns and questions through the patient portal, so they are aware of your concerns. Then they can follow up with you at your next regular visit. Remember, talking about your anus may be embarrassing to you, but medical doctors are used to it.”

Doctors are also used to having frank conversations about sex and anuses, so you don't need to be worried about phasing them. “Talking about symptoms, especially those related to sex, can sometimes feel difficult or embarrassing, but it’s really important to speak up if something is worrying you,” Dr. Sutton says. “Healthcare professionals, particularly those working in sexual health, are very familiar with discussing intimate topics and will do their best to make the conversation as comfortable and easy as possible for you.

If it helps, you can always bring a friend or someone you trust for support. Most importantly, don’t ignore any problems, getting checked early is always the best step for your health.”

Anal cancer resources:

Check out Cheeky Charity to join their biweekly LGBTQ+ anal cancer support group.

Visit AnalCancer.com to learn more and get a guide for talking with your provider.

To find an LGBTQ+ friendly oncologist whois committed to creating a safe and welcoming environment, try The Cancer Network's Welcoming Provider Directory or LGBTQ+ Healthcare Directory.

Sources cited:

Daniel Garza, the director of anal cancer and HPV outreach at Cheeky Charity, and partner with Incyte on Let’s Talk Anal Cancer, a program aimed at normalizing candid conversations about anal cancer and providing critical information, particularly to LGBTQ+ folks.

Dr. Naomi Sutton, who works in the HIV and sexual health space for Sagami.

Andrew Spieldenner, the executive director of MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights.

Is it causing increased shame or stigma about people’s bodies?Pro-stock studio/Shutterstock

Is it causing increased shame or stigma about people’s bodies?Pro-stock studio/Shutterstock