We usually think of historians getting into esoteric intellectual debates, but two medieval scholars are currently arguing over penises.

Yes, you read that correctly.

Oxford University Professor George Garnett and Christopher Monk, an expert on Anglo-Saxon nudity, are currently squabbling over the number of phalluses in an ancient medieval tapestry.

Garnett believes that there are 93 depictions of male genitalia in the Bayeux Tapestry, but Monk believes that he’s miscounting and there is actually one more unaccounted for.

The Bayeux Tapestry, embroidered in the 1070s, consists of nine panels with 58 scenes depicting “the Norman Conquest of England after the Battle of Hastings in 1066,” The Art Newspaper reports.

In a blog post from April 27, Monk claimed that a mystery “appendage dangling below the tunic” of one of the figures on the tapestry is actually a “missed penis” and not a scabbard for a sword.

Back in 2016, Monk published an essay laying out his argument for why he believes “previous commentators seemed to have missed the genitals of this running, club-wielding man.”

Then in 2018, Garnett published an article titled The Bayeux Tapestry with knobs on: what do the tapestry's 93 penises tell us? for History Extra where he explained that there are 93 total penises in the tapestry, five on mean and 88 belonging to horses.

Garnett addressed the controversy again on a recent episode of the BBC History Magazine podcast History Extra where he explained that what Monk thinks is a penis is actually a scabbard with a brass decoration on the tip.

“If you look at what are incontrovertibly penises in the tapestry, none of them have a yellow blob on the end,” he said on the podcast. “What I’ve shown is that this is a serious, learned attempt to comment on the conquest, albeit in code.”

But Monk wrote in his blog post that the tapestry depicts a “testosterone-soaked scene” that “reeks of male hormones” which is why there are not human penises and erect horse phalluses, including the penis (or scabbard) at the heart of the debate.

“Two things: scabbards are not shown in the Bayeux Tapestry with ornamentation at their bottom end – no ‘blobs’; and the position of the dangling appendage is completely wrong for a scabbard,” he explained.

He also said that the way the “penis” in question is rendered is similar to other not-hotly-debated phalluses in the tapestry. “Note that he has the full package of testicles, penis shaft and head,” he said, which could account for the “blob” at the tip.

“One of the most important things when studying detail in early medieval/Anglo-Saxon artwork is to observe patterns. In the case of male genitalia in the Bayeux Tapestry, human and equine, there are patterns for a penis … they are drawn consistently,” Monk wrote.

He continued, “[These are] male genitals, not a scabbard. That’s where the internal, art historical evidence points ... New ideas and theories rise up frequently. Or, put another way, one should never count one’s penises too quickly.”

Monk said he hopes his blog post will “put an end to the academics-at-loggerheads debate.”

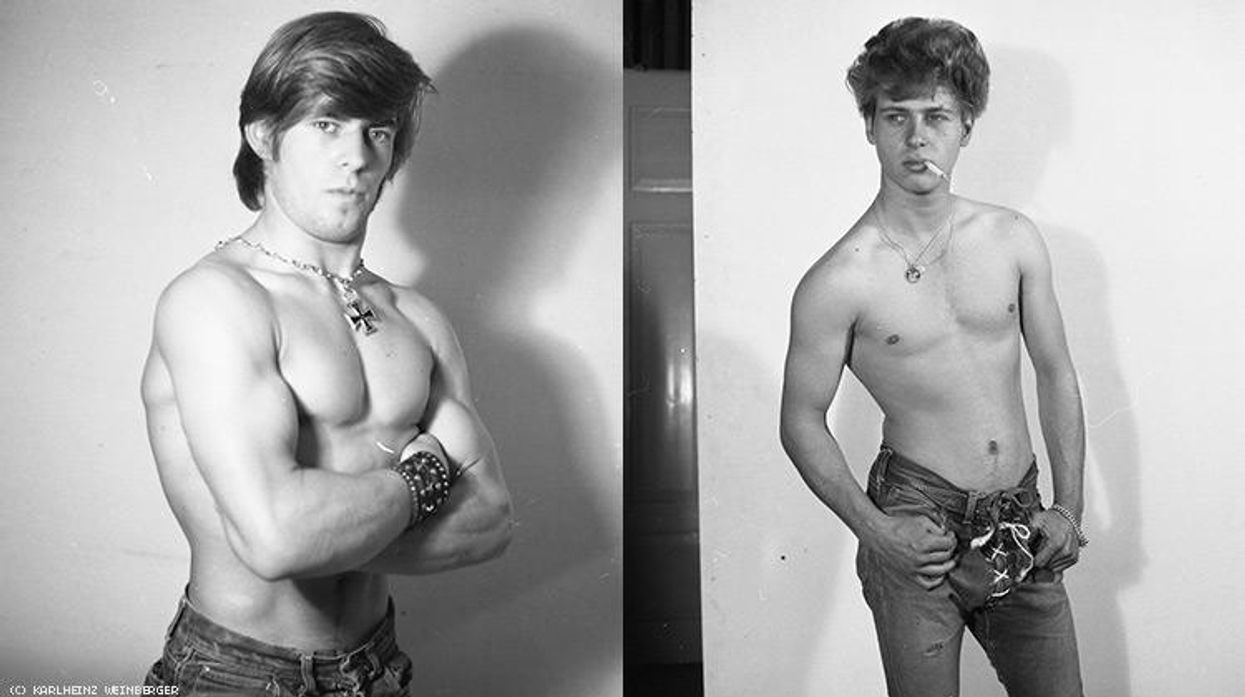

Actress Marlene Dietrich and Paul Porcasi in a scene from the movie Morocco.Donaldson Collection/Getty Images

Actress Marlene Dietrich and Paul Porcasi in a scene from the movie Morocco.Donaldson Collection/Getty Images