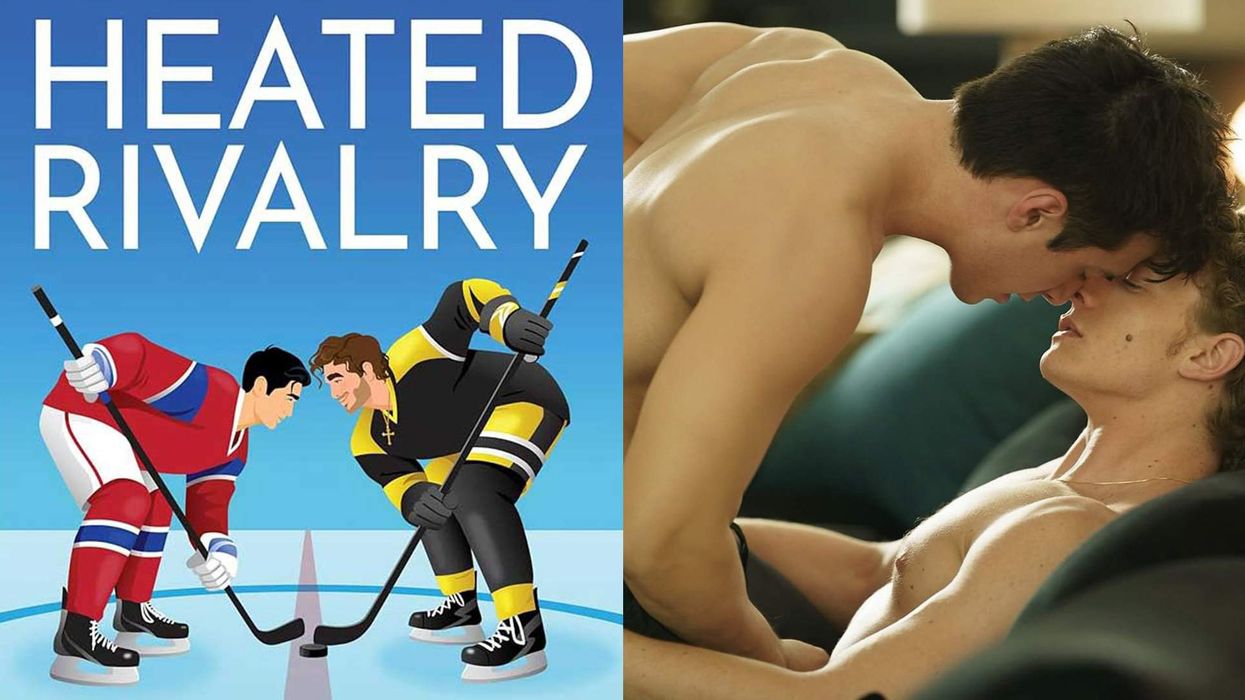

When Patricia Highsmith’s novel about a love affair between a suburban socialite and a younger shopgirl was published in 1952, it was revolutionary in its depiction of healthy, overt female desire and for its hopeful ending. (Spoiler alert: Neither of the women ended up relegated to a mental institution or in a loveless marriage with a man she loathed or dead.) While lurid lesbian pulp with gruesome endings proliferated at the time, Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (also titled Carol and written under the pseudonym Claire Morgan) elevated love between women to the realm of the possible, offering a kind of representation, surely, that very few queer women of the time would have previously known.

More than half a century after The Price of Salt hit bookstores — often bearing a lesbian pulp fiction cover — out screenwriter Phyllis Nagy’s big-screen adaptation of Carol would become revolutionary in its own way. Fifteen years after she first penned it, Nagy’s spare, elliptical screenplay hits theaters Friday, starring Cate Blanchett as the titular character and Rooney Mara as her lover, and directed by Far From Heaven helmer Todd Haynes. It seems absurd that as of this June, marriage equality became the law of the land, and yet Carol may well be the first Oscar-worthy love story about a female couple in which a male lead does not steal focus — and that doesn’t end in shambles for the characters.

“When you think about the movies that have been made, even high-profile movies about men, like Brokeback Mountain, someone died,” Nagy says about the dearth of happy endings for queer characters in big-time Hollywood. “It’s depressing,” she adds. But Nagy's film stands to change that.

A playwright as well as a screenwriter, Nagy, 53, is known for her plays Weldon Rising and Butterfly Kiss, the film Mrs. Harris (starring Annette Bening), and for a stage adaptation of one of Highsmith’s best-known, and gay-themed, novels, The Talented Mr. Ripley. Beyond Nagy’s writing pedigree, her association with Highsmith during the last 10 years of the enfant terrible’s life uniquely qualifies her to get at the underbelly of a Highsmith text. While Carol is one of the few of Highsmith’s 22 novels that don’t feature a charming killer or a heinous crime, the transgression in Carol is, of course, the unabashed consummation of “the love that dare not speak its name.”

Phyllis Nagy

Nagy was a young researcher at The New York Times in the mid-’80s when she was assigned to accompany Highsmith on a walking tour of New York for one of the paper’s now-defunct magazines. Nagy was aware that the novel was somewhat autobiographical, in that Highsmith modeled the young woman Therese (Mara in the film) in part after her own experience; Nagy held off on reading Carol until after Highsmith’s death in 1995.

“This is actually quite radical as a document in [Highsmith’s] profound lack of interest in the usual psychological clichés about people fretting about being gay,” Nagy says she thought after reading the novel. “There’s none of that, and there are three lesbians (including Carol’s best friend and ex-lover, Abby, played by Sarah Paulson in the film). They’re all just pretty much out there behaving.”

Highsmith gained notoriety for her first novel, Strangers on a Train (1948), with Alfred Hitchcock’s adaptation of the first book remaining one of the great psychological thrillers of modern cinema. The Talented Mr. Ripley received several big-screen treatments, including Anthony Minghella’s excellent 1999 interpretation that starred Matt Damon and featured a young Blanchett.

Following Minghella’s sumptuous Ripley, Highsmith became the subject of two biographies — Andrew Wilson’s Beautiful Shadow (2003) and Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss Highsmith (2009), in which both biographers chronicled Highsmith’s love affairs with women and men. In the authors’ depiction of Highsmith, while she was fairly touted as a singular sort of genius, she came off rather less well when it came to personal matters.

“The only consistent things about Highsmith are her tumultuous love affairs, which were nonstop from her teens until a few years before her death at age 74, her unchecked alcoholism, her tireless work ethic, and her misanthropic take on the human race,” columnist Frank Rich recently wrote about her in New York magazine.

Despite Highsmith’s mistrust of people, Nagy formed what she calls “a sweet friendship” with the notorious curmudgeon.

“At the end of a very long and gruesome tour,” Nagy says of the day she met and went on the walking tour with Highsmith, “she pulled a hip flask out of her trench coat, and this is like 11 in the morning, and said, ‘Well. I don’t know about you, but I need a drink,’ and held the flask out as a challenge.”

“It was actually full of scotch, and it was quite a shock at that hour,” Nagy adds. “We had lunch back at her strange hotel. It was just drinking, actually. I don’t think we ever moved on to food.”

That first meeting led to a friendship that continued across the pond when Nagy and Highsmith both happened to be living in London, Nagy says. Nagy adds that she’d been aware of The Price of Salt, a book Highsmith finally claimed as hers 40 years after it was published, but Nagy had been somewhat “terrified” to read it due to its semiautobiographical story.

Like the young woman Therese (Mara in the movie), Highsmith encountered a glamorous suburban socialite in a fur while working a short, miserable stint in the doll department at Bloomingdale’s, according to Rich’s piece. The woman, whom Highsmith could not get out of her mind, had come in to the store to buy a doll for her daughter. She became the impetus for Carol.

Not only did Nagy eventually read the novel, she brought it to life for the screen after a producer asked if she’d take on the adaptation. And she did so with great economy, changing Therese from an aspiring set designer in the novel to that of a budding photographer in the film (a change that obviously fits with the medium of cinema). She also cut out a lengthy second half of the road trip Carol and Therese embark on in which Therese remains in the Midwest while Carol returns to New Jersey to deal with family matters. From script to screen, the film had about a 15-year gestation period with various producers and directors involved at various times, until they landed on the dream team of Blanchett, Mara, Paulson, Kyle Chandler as Carol’s husband, Harge, renowned costume designer Sandy Powell (The Departed, The Wolf of Wall Street) and of course, the auteur Haynes.

In the film, Blanchett plays the elegant, smoldering, sexual Carol with humor and pathos, even as she’s torn asunder trying to hang on to her daughter during an ugly custody battle with her soon-to-be ex-husband, Harge, while honoring her true nature and her love for Therese. The casting of the two-time Oscar winner was such an obvious boon in the process of bringing the film to fruition that when asked how she felt when she heard that news of the casting, Nagy jokes, “Of course I was disappointed, because you know, it was a horrible choice.”

She quickly adds of the casting, “There’s nothing you could do but clap your hands in glee and say ‘Great!’ And then, of course, when these people start to work on it, and you understand everyone is on the same page about what’s necessary, then it’s even better. It’s the best experience you’ll ever have.”

Nagy saves some of her greatest praise for Haynes, whom she credited with the idea for the bookending device toward the beginning and end of the film in which Carol and Therese are at a do-or-die moment in their affair.

“Apart from the fact that he is the loveliest guy,” Nagy says of Haynes. “He is also an absolutely brilliant director and a great collaborator. He ended up being much more protective of the script than I was. Well, that’s not true, but he was immersed in it.”

While Nagy created the bookending scene at Haynes’s suggestion, the more difficult-to-quantify aspect of their collaboration was perhaps in tone. For instance, they agreed that the men in the film should not be vilified, making Chandler the perfect choice to play the outsider husband struggling to understand his own masculinity in light of his wife’s predilections.

“It was really important to Todd, and also to me, that Harge not be cast with anyone who might embody him as a monster. There’s really no reason for that,” Nagy says. “Although it’s not written or made as an agenda film, certainly on my mind was this sort of political thought that you win people over for basically presenting, not judging, people responding to their particular situation. I think that would be the more responsible thing to do than giving him a twirly mustache.”

Another, seemingly simple change in the film was Nagy’s decision to make Therese, who works in the doll department at a Bloomingdale’s-type store, thoroughly uninterested in them. Rather, she conveys her passion for trains to Carol, which inspires the older woman to forgo the doll and buy her daughter a train set.

“It’s one of the things that makes Carol interested, and starts this whole ‘flung out of space thing’ about Therese,” Nagy said, referring to one of the few verbatim lines of dialogue from Highsmith’s novel, when Carol, intrigued, calls Therese a “strange girl, flung out of space.”

It’s no small feat to give life to what is perhaps one of the most famous lesbian-themed novels of all time, but it’s even more impressive that Nagy managed to write her screenplay between the lines of Highsmith’s innuendo-laden novel. The pair doesn’t openly acknowledge mutual attraction throughout much of the film. And yet, Carol and Therese fall deeply in love, as will audiences, with a glimpse of the corner of Carol’s fur, a wisp of smoke issued from Carol’s lips, Therese’s charmingly awkward sip from a martini glass.

While she went back and wrote the bookending device at Haynes’s suggestion, she asked that they keep certain aspects of the love scene that were important to her.

“When writing that scene, there were certain things that I thought needed to happen in order for it to be realistic, that it take place in a very ordinary environment, and that there is an awkwardness to it that is touching and hot rather than funny,” Nagy explains.

For all of the collaboration and for the universality of its love story that will surely cut across gender and sexuality for many, Carol remains a very specific depiction of love between women. When Carol beholds Therese’s naked body, for being the more experienced woman, she exhibits great vulnerability.

“I asked Todd to keep Carol’s line when she sees Therese and says, ‘I never looked like that,” Nagy says. “Because it’s about the way that women relate to each other, that of course no guy would know, Todd or anyone.”

Cindy Ord/Getty Images

Cindy Ord/Getty Images