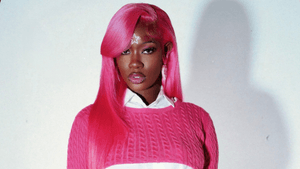

The historical legacy of the devaluation and demonization of black motherhood was both applauded and rewarded at this years Oscars. And the point was clearly illustrated with Mo’Nique, capturing the gold statue for best supporting actress in the movie Precious, based on the novel Push by Sapphire, as a ghetto welfare mom who demeans and demoralizes her child at every turn.

Mo’Nique’s role juxtaposed with Sandra Bullock’s, who captured her Oscar as best actress in the movie The Blind Side, offers the hand of human kindness to a poor black child in need of parenting.

But the images African- Americans parenting have historically been viewed through a prism of gendered and racial stereotypes. And the image of Mo’Nique as the bad black mother and Sandra Bullock as good white mother is not new.

The images of the bad black mothers have not only been used for entertainment purposes but also used for legislating welfare policy reforms.

For example, in Ronald Regan’s era (1981- 1989), black motherhood was constantly under siege. These moms were depicted as Cadillac-driving “ welfare queens,” who had little to no ambition to work, wanted money for drugs and wanted to continue, due to their uncontrolled sexuality, to have illegitimate babies in order to remain on welfare.

Reagan told a fallacious story about a African American mother from Chicago's South Side who was arrested for welfare fraud that subsequently not only shaped public perception of black mothers but also shaped welfare reform:

"She has 80 names, 30 addresses, 12 Social Security cards and is collecting veteran's benefits on four non-existing deceased husbands. And she is collecting Social Security on her cards. She's got Medicaid, getting food stamps, and she is collecting welfare under each of her names."

The story of Precious takes place in 1983. While the book shapes the character Precious and Precious’ mom Mary within both the economic and cultural context of the Reagan era, the movie Precious does not. And this one-dimensional depiction of Mary conveniently re-inscribes black mothers’ fears that haunt us daily -- we’re never good enough.

The feeling that we as mothers are never good enough was thrown in our faces also in Daniel Moynihan’s 1965 report The Negro Family: The Case For National Action. This report also known as the Moynihan Report states that the cause of the destruction of the Black nuclear family structure were women, giving rise to the myth of "the Black Matriarch.” The myth proposes that African-American women are complicit with white patriarchal society in the emasculation of African-American men by becoming heads of households and primary jobholders.

Lee Daniels, Precious’ director, has a knack for portraying monstrous black mothers on the silver screen as he was a producer on Monster’s Ball, the 2001 film for which Halle Berry, playing a bad mother, won the Academy Award for Best Actress.

More on next page...

\\\

(continued)

In this “post-racial” Obama era, the subject of race and the politics of black representation in films are constrained by neither political correctness nor moral consciousness. Daniels would argue that the moral conscious of his Precious is evident in the film's crossover appeal and also in the universality of its message -- the suffering and damage of child molestation at the hands of parents.

While Daniels’ film shocked and awed moviegoers across the country, many African American sisters like Precious didn’t find the film as liberating and cathartic as intended.

And much of the reason is because, for many of these sisters, as with a lot of African American women, we saw not ourselves but rather a modern-day version of an old racist stereotype.

Some African American woman told me they saw the character Precious as our culture’s new “Hottentot Venus.” Hottetot Venus was Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman from South Africa, who was forced to reveal her huge buttocks and labia to curious Europeans in a traveling human circus show. The Hottentot Venus has become the iconic image for portraying black female bodies as subhuman, and this image is still very much part and parcel of our culture’s social discourse.

“Portraying African-American women as stereotypical mammies, matriarchs, welfare recipients, and hot mommas has been essential to the political economy of domination fostering Black women’s oppression, ” sociologist Patricia Hill Collins writes in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment.

Precious is no doubt an important film. But when the artistic portrayal of the characters and people Daniels is trying to bring to life in a new way re-inscribes century-old stereotypes, Daniels, albeit with good intent, has caused harm.

And if Daniels won’t take my advice on this then he should just pause for a moment and go and ask his momma.

Get more from Rev. Irene here!

Cindy Ord/Getty Images

Cindy Ord/Getty Images