Kath Buckell is not only a singer-songwriter, she’s a bridge builder — between people, cultures, and genres of music.

“We all come from different places, but we all have something that connects us, which is the beauty of the human race and our connection to our environment,” says the 24-year-old Australian-born performer, who released a new album, Faces Do Not Change, this fall, and has a full schedule of concerts coming up.

Buckell, who now lives in New York City, might be best classified as a folksinger, as she’s been compared to such folkie icons as Joan Baez and Judy Collins, both of whom she admires greatly, along with other faves such as Bob Dylan and Van Morrison. But her work also draws on rock, blues, country, and the traditional music of various cultures, and she delivers complex, meaningful lyrics in a haunting, mellifluous voice.

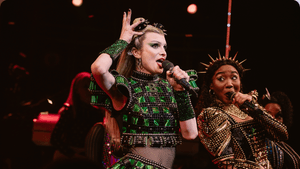

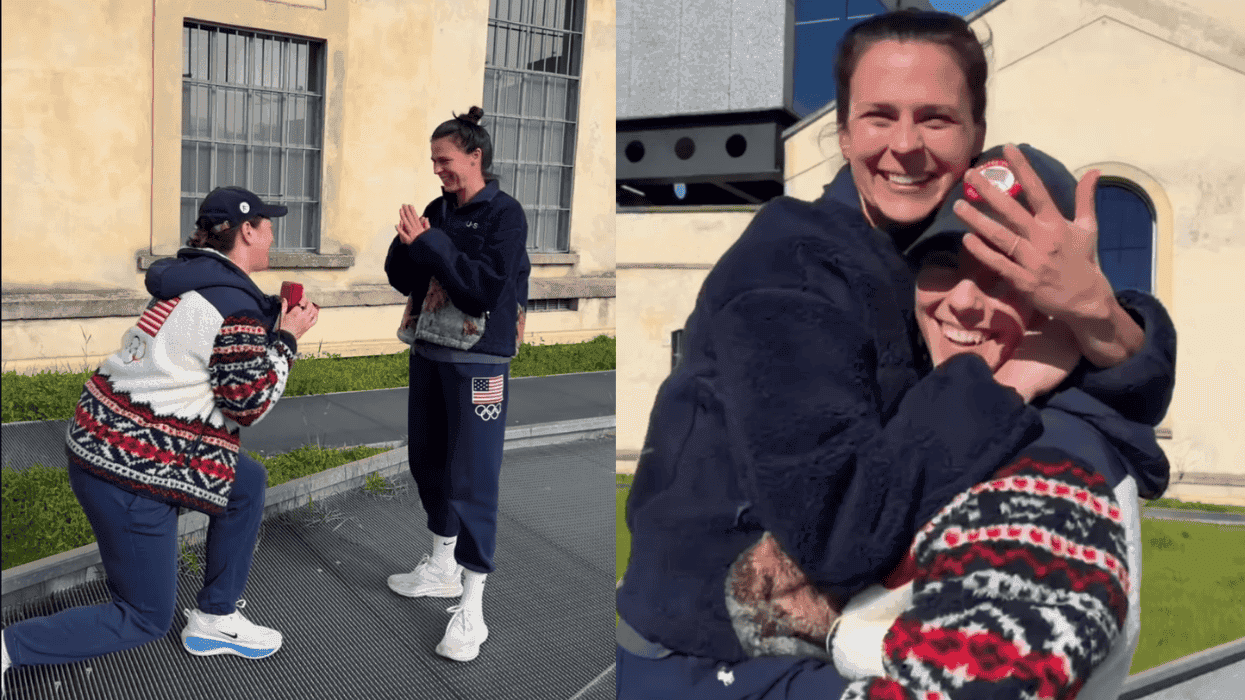

She performs both solo and as a member of the Jammin Divas, a multicultural four-woman band that is a perfect example of bridge building. Besides Buckell, there’s Aoife Clancy, who is Irish and the daughter of Bobby Clancy of the legendary musical group the Clancy Brothers; Becky Chace, an American; and Hadar Noiberg, who hails from Israel and is also Buckell’s life partner. The group, Buckell says, is a very special collaboration of women from different backgrounds coming together to play traditional and contemporary music.

Faces Do Not Change, a solo album produced by Daniel Jakubovic, represents Buckell’s effort to explore her Australian heritage and bring it to her audience. For several of the tracks, Buckell set to music the words of notable and radical Australian poets A.B. “Banjo” Paterson, Henry Lawson, and Dame Mary Gilmore. “I wanted people to experience a bit of the roots and the culture of Australia,” she says.

Of the three, Paterson is perhaps best known outside Australia, or at least one of his works is: His poem “Waltzing Matilda,” set to a traditional tune, has become an internationally beloved song, even among those of us who don’t know what a swagman or a billabong is. For her album, Buckell uses his “Song of the Wheat,” one of several Paterson poems that express his love for the people and landscape of the Australian bush, a term used to describe the nation’s rural areas, central to the formation of Australia’s national identity.

more on next page...

\\\

(continued)

The three Lawson-based works on the album include “Weary Drover,” derived from Lawson’s “Ballad of a Drover,” another ode to the hardworking people of the bush. Two songs use Gilmore’s verse, including “No Foe Shall Gather Our Harvest,” based on Gilmore’s 1940 poem asserting Australian identity and patriotism during World War II.

Buckell does not shy away from the sadder aspects of her nation’s history, either: “Orphaned by the Color of My Skin,” with original lyrics by Buckell, deals with the indigenous children of Australia who were removed from their homes by the government to be raised by white families, a practice that endured from the early 20th century until the 1960s. These children came to be known as the “stolen generations,” and Buckell’s song was inspired by one woman’s autobiographical account, Orphaned By the Colour of My Skin: A Stolen Generation Story.

The song reflects Buckell’s passion for social justice, a passion she brings to bear on LGBT rights and other issues. “It’s the rigidity and judgment that can cause segregation and factioning that are really unacceptable,” she says.

Among instances of that judgment, the singer, who lived in Israel for a time, recalls seeing antigay protesters at Pride parades in Jerusalem. An Israeli acquaintance translated some of the protesters’ words for Buckell, who found out the demonstrators were saying gay people should be put in institutions and chanting slogans such as “Holy Land, not homo land.”

Buckell saw a bit of anti-LGBT antagonism in Kyabram, the small Australian town where she grew up, a farming community in the northern part of the state of Victoria. Not from her family, however: “As long as I’m happy, they’re happy,” she says, adding that they treat Noiberg as their daughter.

Buckell and Noiberg have been together about four years. Buckell, who had an earlier relationship with a man, eschews labels for her sexuality, although she thinks labels are fine for people who are comfortable with them. “I see beauty in all people and can have a deep connection whether they’re male or female,” she says.

Being partners both personally and professionally might seem challenging, but Buckell says it’s been a positive experience for her and Noiberg. “It’s a good challenge, because we really have a good sense of what’s professional and what’s personal,” she says. “We’ve really had a good balance.”

Up next for Buckell: She has an idea for a new album, inspired by the diary of an ancestor who married a British lord, and she’s going to be touring extensively in the coming year. She and Clancy will perform New Year’s Eve at the Zeiterion Theatre in New Bedford, Mass., and January 16 she’ll have a record release show for Faces Do Not Change at Rockwood Music Hall in New York City. She also has several winter and spring dates scheduled with the Jammin Divas. For a full list of concerts, and to sample her music, go to KathBuckell.com.

Cindy Ord/Getty Images

Cindy Ord/Getty Images